Why multi-stage screening is essential

Many pathogens have a window period: shortly after infection an antibody test may still be negative while PCR/NAT can already detect the agent. Therefore reputable programmes combine medical history, serological tests, PCR/NAT and a delayed release after repeat testing (commonly 90–180 days). This approach noticeably reduces the residual risk. This logic follows the framework recommendations of ESHRE and public health authorities such as UKHSA.

Viruses that can be detected in ejaculate

- HIV – antigen/antibody combination test plus PCR/NAT; release only after a second blood sample.

- Hepatitis B and C – HBsAg, anti-HBc, anti-HCV and HCV-NAT; chronic infection must be reliably excluded.

- CMV – IgG/IgM and PCR if indicated; relevant during pregnancy.

- HTLV I/II – rare, but included in many programmes.

- HSV-1/2 – clinical history, PCR if suspected.

- HPV – PCR for high-risk types; positive samples are discarded.

- Zika, dengue, West Nile – travel history, RT-PCR if needed and deferral after stays in endemic areas.

- SARS-CoV-2 – currently mainly medical history and symptom checks; programme requirements vary.

Bacteria and parasites in the context of sperm donation

- Chlamydia trachomatis – often asymptomatic; NAAT from urine or swab.

- Neisseria gonorrhoeae – NAAT or culture with resistance testing.

- Treponema pallidum (syphilis) – TPPA/TPHA and activity markers (e.g. VDRL/RPR).

- Trichomonas vaginalis – NAAT; can reduce sperm function.

- Ureaplasma/Mycoplasma – treated when detected.

- Uropathogenic organisms (e.g. E. coli, enterococci) – culture if suspected; problematic strains are excluded.

Genetic risks: current standard testing

- Cystic fibrosis (CFTR)

- Spinal muscular atrophy (SMN1)

- Haemoglobinopathies (sickle cell, thalassaemias)

- Fragile X (FMR1) depending on history

- Y-chromosome microdeletions in marked oligo/azoospermia

- Population-specific panels (e.g. Gaucher, Tay–Sachs)

Extended testing is guided by family history and ancestry. ESHRE recommends defining indication areas transparently.

Risk matrix: pathogen, test, window period, release

| Erreger | Primärtest | Fensterperiode | Typische Freigabe | Bemerkung |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV | Ag/Ab-Kombi + PCR/NAT | Tage bis wenige Wochen | Nach Retest (90–180 Tage) | NAT verkürzt Unsicherheit |

| HBV/HCV | HBsAg, Anti-HBc, Anti-HCV, HCV-NAT | Wochen | Nach Retest | HBV-Impfstatus prüfen |

| Syphilis | TPPA/TPHA + Aktivitätsmarker | 2–6 Wochen | Nur bei kompletter Serologie negativ | Therapie → Deferral bis Ausheilung |

| Chlamydien/Gonorrhö | NAAT (Urin/Abstrich) | Tage | Bei Negativbefund | Positiv → Therapie, Kontrolltest |

| CMV | IgG/IgM ± PCR | Wochen | Bankabhängig | Relevanz in der Schwangerschaft |

| Zika/West-Nil | RT-PCR + Reiseanamnese | Wochen | Deferral nach Reise/Infekt | Endemiegebiete beachten |

Specific timeframes vary by laboratory and national requirements. Guidance is provided by ESHRE, UKHSA and the EU tissue directives.

How the screening process works

- Medical history and risk assessment – questionnaire, travel and sexual history.

- Laboratory tests – combination of antibody/antigen and PCR/NAT.

- Genetic panel – according to guidelines and history.

- Quarantine – freezing and delayed release after repeat testing.

- Final release – only when all results are clear.

Private sperm donation: how to stay safe

- Current written test evidence from both parties (HIV, HBV/HCV, syphilis, chlamydia/gonorrhoea; depending on circumstances CMV, trichomonas).

- No unprotected sex with third parties during the window period after tests.

- Use only sterile single-use containers, clean surface, wash hands; do not mix samples.

- Document date, time and test results; agree arrangements in writing.

- If symptoms such as fever, rash or discharge occur, postpone donation and seek medical advice.

Medical background on STI prevention: CDC and UKHSA provide accessible overviews.

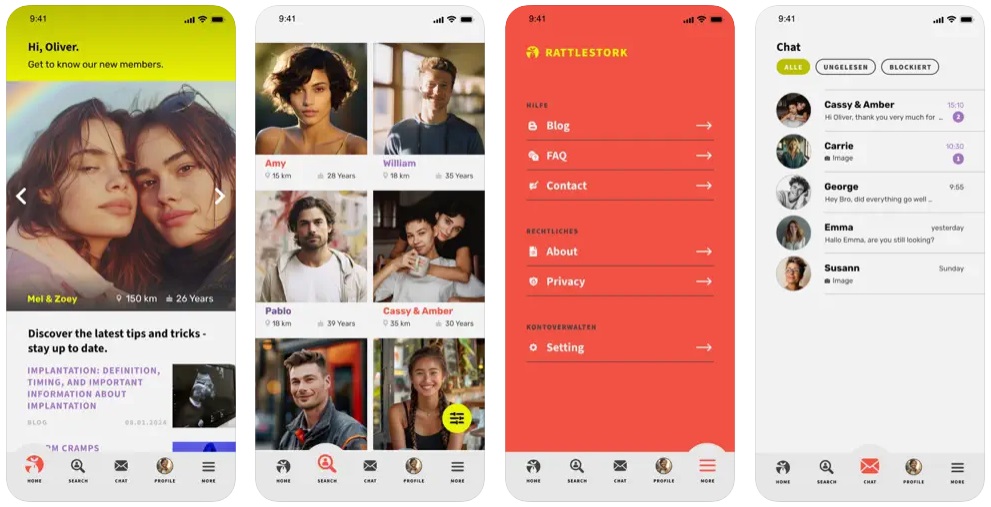

Sperm donation with RattleStork: organised, documented, safety-focused

RattleStork helps you plan a private sperm donation responsibly. You can exchange test evidence securely, set reminders for retests, use single-use material checklists and document individual consents. Our practical checklist guides preparation, clean collection and handover. This keeps the donation planned and transparent while maintaining safety standards.

Law and standards (UK/Europe)

In the UK, the collection, testing and provision of donor gametes are regulated by national law and overseen by bodies such as the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA). Clinical and laboratory standards are informed by guidance from the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA), professional organisations like ESHRE and, where applicable, EU directives on tissues and cells. Many banks also limit the number of children per donor and maintain registers.

Conclusion

Reputable sperm banks combine medical history, serological tests, PCR/NAT, quarantine and retesting. This makes infections and genetic risks very rare. For private donations the same principles are essential: up-to-date tests, attention to window periods, hygiene, documentation and clear agreements. RattleStork offers structured support to enable a safe, responsible sperm donation.