Why multi-step screening is essential

Many pathogens have a window period: shortly after infection an antibody test may still be negative while PCR/NAT can already detect the pathogen. That is why reputable programs combine medical history, serological tests, PCR/NAT and a delayed release after retesting (often 90–180 days). This approach reduces residual risk substantially. This logic follows guidance from professional societies such as ESHRE and national public health authorities.

Viruses that can be detectable in ejaculate

- HIV – antigen/antibody combination test plus PCR/NAT; release only after a second blood sample.

- Hepatitis B and C – HBsAg, anti-HBc, anti-HCV and HCV-NAT; chronic infections must be reliably excluded.

- CMV – IgG/IgM and PCR if indicated; relevant in pregnancy.

- HTLV I/II – rare, but included in many programs.

- HSV-1/2 – clinical history, PCR if suspected.

- HPV – PCR for high-risk types; positive samples are discarded.

- Zika, Dengue, West Nile – travel history, PCR as needed and deferral after stays in endemic areas.

- SARS-CoV-2 – currently managed mainly by history and symptom screening; program requirements vary.

Bacteria and parasites in the context of sperm donation

- Chlamydia trachomatis – often asymptomatic; NAAT from urine or swab.

- Neisseria gonorrhoeae – NAAT or culture with resistance testing.

- Treponema pallidum (syphilis) – TPPA/TPHA and activity markers (e.g., VDRL/RPR).

- Trichomonas vaginalis – NAAT; can impair sperm function.

- Ureaplasma/Mycoplasma – treat specifically if detected.

- Uropathogens (e.g., E. coli, enterococci) – culture if suspected; problematic strains are excluded.

Genetic risks: current standard testing

- Cystic fibrosis (CFTR)

- Spinal muscular atrophy (SMN1)

- Hemoglobinopathies (sickle cell, thalassemias)

- Fragile X (FMR1) depending on history

- Y-chromosome microdeletions in severe oligo/azoospermia

- Population-specific panels (e.g., Gaucher, Tay–Sachs)

Expanded testing is guided by family history and ancestry. ESHRE recommends defining indication areas transparently.

Risk matrix: pathogen, test, window period, release

| Pathogen | Primary test | Window period | Typical release | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV | Ag/Ab combo + PCR/NAT | Days to a few weeks | After retest (90–180 days) | NAT shortens uncertainty |

| HBV/HCV | HBsAg, anti-HBc, anti-HCV, HCV-NAT | Weeks | After retest | Check HBV vaccination status |

| Syphilis | TPPA/TPHA + activity markers | 2–6 weeks | Only if complete serology is negative | Treatment → deferral until resolved |

| Chlamydia/Gonorrhea | NAAT (urine/swab) | Days | With negative result | Positive → treatment, follow-up test |

| CMV | IgG/IgM ± PCR | Weeks | Depends on the bank | Relevant in pregnancy |

| Zika/West Nile | RT-PCR + travel history | Weeks | Deferral after travel/infection | Observe endemic areas |

Specific timeframes vary by laboratory and national regulations. Guidance is provided by professional bodies such as ESHRE, national public health authorities (e.g., CDC) and EU tissue directives.

How the screening process works

- Medical history and risk assessment – questionnaire, travel and sexual history.

- Laboratory tests – combination of antibody/antigen and PCR/NAT.

- Genetic panel – according to guidelines and personal history.

- Quarantine – freezing and delayed release after retesting.

- Final release – only with completely normal results.

Private sperm donation: how to stay safe

- Current written test results from both parties (HIV, HBV/HCV, syphilis, chlamydia/gonorrhea; depending on circumstances CMV, trichomonas).

- No unprotected sex with third parties during the window period after testing.

- Only sterile single-use containers, clean surface, wash hands; do not mix samples.

- Document date, time, and test results; put agreements in writing.

- If symptoms such as fever, rash or discharge occur, postpone donation and seek medical advice.

Medical background on STI prevention: CDC and national public health authorities offer accessible overviews.

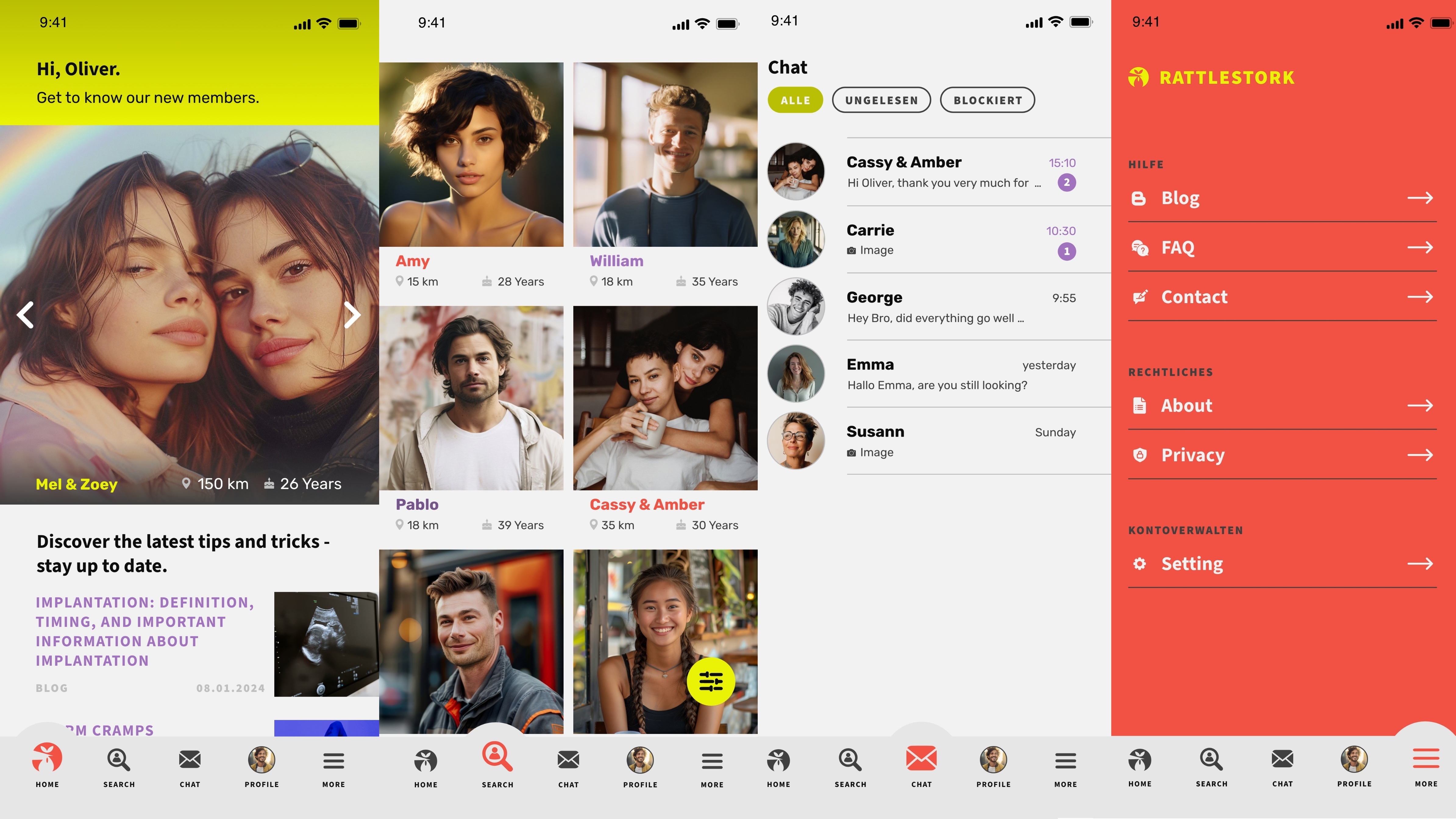

Sperm donation with RattleStork: organized, documented, safety-focused

RattleStork helps you plan a private sperm donation responsibly. You can securely exchange test results, set reminders for retests, use single-use material checklists and document individual consents. Our practical checklist guides preparation, clean collection and handover. This keeps the donation predictable and transparent while maintaining safety standards.

Law and standards

Regulation of collection, testing and distribution of donor gametes varies by country. In the United States oversight can involve agencies such as the FDA for tissue regulation and the CDC for infectious disease guidance, while professional societies like ASRM and ESHRE provide clinical standards. Many banks additionally limit the number of children per donor and maintain registries.

Conclusion

Reputable sperm banks combine medical history, serology, PCR/NAT, quarantine and retests. This makes infections and genetic risks very rare. The same principles are crucial for private donations: up-to-date testing, respect for window periods, hygiene, documentation and clear agreements. RattleStork provides structured support for a safe, responsible sperm donation.