Key terms and guiding principles

Hifẓ al‑nasl (protection of progeny): Among the Maqāṣid al‑Sharīʿa is the protection of lineage. It requires clear origin, the avoidance of mixing lineages, and the safeguarding of the child’s rights.

“Al‑walad li‑l‑firāsh” – the child belongs to the marital bed: Lineage is attributed to the marital context. Third‑party donations undermine this principle because genetic and social parenthood diverge.

Marriage as a prerequisite: Assisted reproduction is permissible when semen, oocytes, and uterus belong to the lawfully married couple and the marriage persists.

Sadd al‑dhara’i (blocking harmful means): Anonymous donations, surrogacy, and commercial models are rejected to protect lineage, family order, and the child’s welfare.

Legal schools and currents

Sunni legal schools (Hanafi, Maliki, Shafi‘i, Hanbali)

There is broad agreement: neither sperm nor egg donation nor surrogacy is allowed. Techniques such as in‑vitro fertilisation (IVF) or intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) are considered permissible so long as all biological contributions come from the couple themselves and the marriage continues (NCBI Bookshelf).

Shi‘i legal tradition (Jaʿfarī school)

Some Shi‘i scholars discuss narrowly defined exceptions if lineage is clearly documented, anonymity is excluded, and rights and duties are contractually regulated. Iran is the formative practical example here: embryo donation has been legal since 2003; sperm donation is not explicitly regulated by a parliamentary act but is discussed in religious‑legal terms (PMC).

Other currents

Ibadi tradition (Oman): highly conservative, close to the Sunni baseline.

Zaydi tradition (Yemen): emphasises clear lineage; third‑party involvement is largely rejected.

Ismaili communities: discuss modern reproductive questions and, in practice, prioritise maximum transparency and documentation.

Salafi and Ahl al‑Hadith currents: reject any third‑party involvement to preserve lineage and the marital order.

Sources and authoritative bodies

Alongside classical fiqh works, fatwa councils and fiqh academies shape modern assessments. The International Islamic Fiqh Academy (OIC) states: assisted reproduction is allowed within marriage; third‑party involvement and surrogacy are prohibited; frozen material may be used only while the marriage remains in force (IIFA resolutions). Country overviews and practice comparisons are provided, for example, by the Middle East Fertility Society Journal (review).

Assisted reproduction, sperm donation and related procedures

Assisted insemination with the husband’s semen (AIH)

Permissible in all schools while the marriage persists, lineage remains clear, and no third party is involved.

Assisted insemination with donor sperm (AID)

Largely impermissible because it separates genetic from social fatherhood. Shi‘i debates mention tightly limited cases, but never anonymous and never commercial.

Surrogacy

Rejected in almost all schools — even when the couple’s gametes are used — as a third uterus is involved and motherhood/lineage becomes unclear.

Cryopreservation

Allowed as long as the marriage continues; after divorce or death, use is disallowed (PubMed).

Pre‑implantation genetic testing (PGD/PGT)

Accepted for a medical indication, for example to prevent serious hereditary disease; non‑medical selection (e.g., by sex) is widely rejected.

Country profiles and regional practice

Arabian Peninsula and Eastern Mediterranean: In Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Kuwait, Bahrain, Oman, Jordan and Lebanon, clinical practice aligns closely with decisions of religious academies. Fertilisation with the couple’s own material within marriage is allowed; third‑party sperm donation and surrogacy are considered incompatible. Oman follows a conservative line due to the Ibadi tradition. In confessionally mixed contexts — such as Lebanon — internal debates exist; provision remains largely restrictive.

North Africa: Egypt, Morocco, Tunisia and Algeria largely follow Al‑Azhar’s line. Third‑party donation and surrogacy are prohibited; assisted reproduction within marriage is widespread. Reform approaches are discussed without changing the fundamental stance.

Türkiye: Third‑party donation is prohibited by law; IVF and ICSI with the couple’s own gametes are permitted. Some couples seek treatment abroad, raising questions for cross‑border reproductive medicine.

Iran: Embryo donation has been legally regulated since 2003. Sperm donation is not expressly permitted by parliamentary statute, but is discussed by individual scholars under conditions. Key points include disclosure, inheritance and guardianship.

Malaysia: National health guidelines and fatwas prohibit sperm and egg donation, but allow assisted reproduction within marriage. The country is an example of coherent rules.

Indonesia: Under state law and fatwas of the Ulema Council, sperm donation and surrogacy are banned. IVF within the marital framework is allowed and established in major clinics.

Diaspora in Europe and North America: Medically, donation and surrogacy are available; religiously, they remain contested. Many Muslim couples choose procedures using their own material, transparent documentation of origin, and pastoral support. In the UK, for example, the HFEA provides clear rules on information access for donor‑conceived people.

Summary table by country (indicative, religious‑ethical practice)

This table summarises religious‑ethical guidance (not legal advice). Determinative sources include fatwas, clinic policies and national regulations. Always check current local requirements.

| Country/region | Majority orientation | Third‑party donation (sperm/egg) | IVF/ICSI (own gametes) | Surrogacy | Note (practice) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saudi Arabia | Sunni | Prohibited | Permitted | Prohibited | Line close to IIFA/OIC. |

| United Arab Emirates | Sunni | Prohibited | Permitted | Largely prohibited | Strict proof of marriage and licensing. |

| Qatar | Sunni | Prohibited | Permitted | Prohibited | Public clinics with clear policies. |

| Kuwait | Sunni | Prohibited | Permitted | Prohibited | Ethics councils shape practice. |

| Bahrain | Mixed | Largely prohibited | Permitted | Prohibited | Confessionally diverse practice. |

| Oman | Ibadi/Sunni | Prohibited | Permitted | Prohibited | Conservative implementation. |

| Jordan | Sunni | Prohibited | Permitted | Prohibited | Fatwa‑guided clinical practice. |

| Lebanon | Mixed | Largely prohibited | Permitted | Prohibited | Shi‘i debates on exceptions. |

| Egypt | Sunni | Prohibited | Permitted | Prohibited | Al‑Azhar shapes guidance. |

| Morocco | Sunni | Prohibited | Permitted | Prohibited | Rules developing. |

| Tunisia | Sunni | Largely prohibited | Permitted | Prohibited | Reform history, yet restrictive. |

| Algeria | Sunni | Prohibited | Permitted | Prohibited | Conservative clinical practice. |

| Türkiye | Sunni | Prohibited | Permitted | Prohibited | Statutory ban on third‑party donation. |

| Iran | Shi‘i | Debated/restrictive | Permitted | Largely prohibited | Embryo donation legal (2003). |

| Pakistan | Sunni | Prohibited | Permitted | Prohibited | Regional availability varies. |

| Bangladesh | Sunni | Prohibited | Permitted | Prohibited | Procedures aligned with fatwas. |

| Malaysia | Sunni | Prohibited | Permitted | Prohibited | Clear national and clinic guidance. |

| Indonesia | Sunni | Prohibited | Permitted | Prohibited | Law/fatwas prohibit donation. |

| Europe/North America | Mixed | Medically available; religiously rejected | Permitted | Religiously rejected | Open documentation rather than anonymity. |

Diaspora and clinical reality

In Western countries, Muslim couples face specific decisions. Medically, donation and surrogacy are available; religiously, they are contested. Approaches that have proved workable include procedures using the couple’s own material, transparent documentation of origin, and pastoral support. As an ethical reference point for information and disclosure, see the ESHRE guidance on information provision; in the UK, the HFEA regulates access rights.

Practical checklist

- Marriage and attribution: Evidence that semen, oocyte and uterus belong to the couple; use of frozen embryos only while the marriage exists.

- Open origin: Where origin‑disclosure models are used, ensure documentation and traceability, with the child’s right to relevant health information (see HFEA).

- Contractual safeguards: Clearly regulate parentage, maintenance, and inheritance/guardianship; document consents transparently.

- Religious counselling: Early pastoral support strengthens trust and facilitates decisions.

- No commercialisation: Only reasonable expenses; no profit‑making or exploitation.

- Medical indication: Pre‑implantation testing strictly for health necessity.

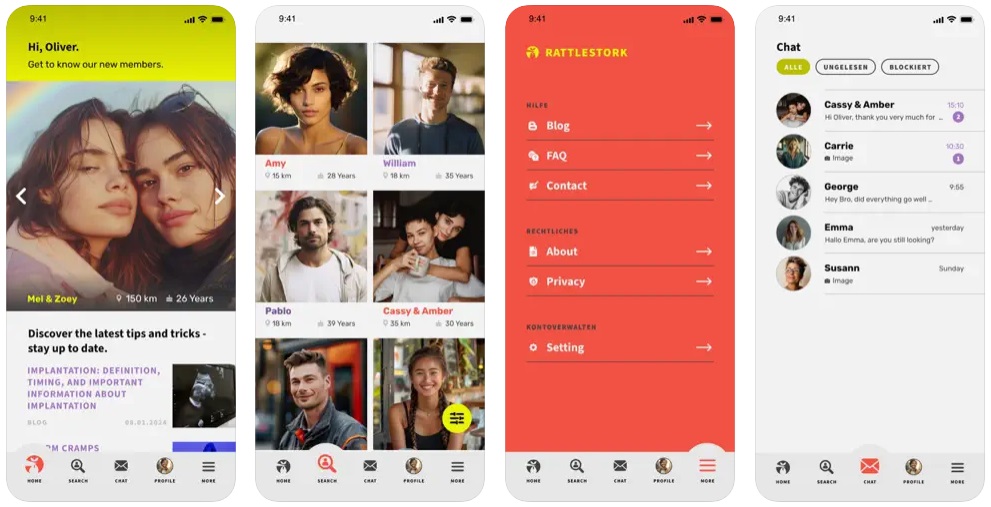

RattleStork – planning responsibly within an Islamic framework

RattleStork helps organise fertility steps with religious sensitivity, transparency and solid documentation — e.g., AIH/IVF using the couple’s own material and, where religiously and legally permissible, open, non‑anonymous models. Verified profiles, secure conversations, and tools for appointments, notes and checklists support a halal‑oriented plan. RattleStork does not provide medical or legal advice and does not replace a fatwa.

Conclusion

The overwhelming majority of Islamic positions reject sperm donation and surrogacy; procedures using the couple’s own gametes within an existing marriage are allowed. In Shi‘i debates there are narrowly defined exceptions — notably embryo donation in Iran — but always with strict lineage safeguards and without anonymity. Overarching constants remain the protection of lineage, marriage as the framework, avoidance of commercialisation, and robust documentation. Further reading: NCBI Bookshelf, PubMed, IIFA resolutions, MEFJ review and the WHO.