Pioneer Era 1784–1909: Canine Experiments, Quill Devices & the Pancoast Scandal

In 1784, Italian scientist Lazzaro Spallanzani showed with dogs that fertilization can occur without intercourse. In 1790, John Hunter in London was rumored to have inseminated a human using his partner’s sperm—allegedly with a quill device in the bedroom.

The first documented donor case is the Pancoast case (1884) in Philadelphia: A physician recruited a “healthy” medical student, paid him $5 plus a steak, and inseminated the patient in secret. The story surfaced in a 1909 anonymous report—pure medical thriller.

- No consent from the woman—the procedure was disguised as routine treatment.

- Selection based on “appearance & health”—early, ethically dubious criteria.

- The child was born healthy; the mother never learned of the donation.

1910–1940: Hidden Practices & Early Clinical Protocols

Between 1910 and 1940, donor insemination was already practiced in some clinics—mostly discreetly, seldom published. Doctors often recorded procedures as “sterility therapy,” and donor details were locked away in sealed files. Only sporadic case reports appeared in journals, often without naming the donors.

- 1914: U.S. physician Addison Davis Hard reported “artificial insemination” cases—still lacking clear terminology.

- 1930s Britain saw the first structured protocols emerge, though public debate remained muted.

- In the Soviet Union, Ilya Ivanov even attempted human‑chimpanzee hybrid experiments—spectacularly unsuccessful.

Freezing as Game Changer: Glycerol & Cryopreservation from 1949

In 1949, researchers discovered the protective effect of glycerol, allowing sperm to survive freezing without crystallizing. In 1953–54, Raymond Bunge and Jerome K. Sherman in Iowa reported the first birth after thawing—ushering in the modern sperm bank.

- Storage at –196 °C in liquid nitrogen.

- Australia reported a baby born in 2020 from sperm frozen for over 40 years—a long‑term record.

- Today’s “straws” trace back to a NASA engineer who was freezing fuel samples.

1960s–1970s: First Formal Sperm Banks & Clinic Networks

In the 1960s, university hospitals in the U.S., U.K., and Scandinavia set up small sperm repositories. In Germany, university clinics (e.g., Kiel) ran internal sperm depots mainly for their own patients. Publicly, the topic remained sensitive, often labeled “sterility treatment.”

- 1964: First reports of standardized lab protocols for sperm washing before IUI.

- 1969: The “Sperm Bank of New York” was described in a U.S. paper—complete with handwritten index cards.

- 1973: Denmark began organizing donor programs outside clinics—laying the groundwork for future exports.

Commercial Boom: Catalogs, “Genius Bank” & HIV Screenings (1970s–2000s)

In the 1970s, sperm donation turned into big business: the California Cryobank (1977) shipped samples nationwide on dry ice, and Cryos International in Denmark began exporting globally. In 1980, millionaire Robert Graham founded the famed Repository for Germinal Choice—nicknamed the “Nobel Prize Sperm Bank.”

- Catalogs listed eye color, hobbies, and degrees—later adding “celebrity look‑alike” filters.

- During the 1980s HIV crisis, a six‑month quarantine plus dual testing became the global standard.

- Family limits (e.g., 10 families per donor in the U.K.) aimed to prevent undiscovered half‑sibling clusters.

2000s to Today: DNA Tests, Scandals & Global Half‑Siblings

At‑home DNA kits made anonymity an illusion. Three cases made headlines worldwide:

- Donald Cline (USA): A physician used his own sperm—fathering over 90 children, uncovered by DNA matches.

- Jan Karbaat (Netherlands): At least 79 offspring conceived with his own sperm.

- “Donor 150” (U.K.): Over 150 children from a single student—before strict donor limits were enforced.

Meanwhile, half‑siblings connect globally: in forums and apps, dozens to hundreds of donor‑conceived individuals share photos, stories, and health information—a phenomenon of the past 15 years.

Oddities & Records in the World of Sperm Donation

- Longest Storage: Over 40 years of frozen sperm—yet a healthy baby was born.

- Farthest Journey: Samples flown from Denmark to Australia—global shipping is routine.

- “Steak & $5”: How the student in the Pancoast case was compensated—including dinner.

- Genius Bank Myth: The “Nobel Bank” boasted laureates—most donors were top students, not Nobel winners.

- NASA Connection: Space‑grade freeze tubes inspired modern lab logistics.

Future of Sperm Donation: IVG, Smart Matching & Cryo Records

- In Vitro Gametogenesis (IVG): Creating sperm from skin or blood cells—still lab research but no longer science fiction.

- Smart Matching: Algorithms compare genetic markers, blood types, and health risks in seconds—no more flipping through catalogs.

- Logistics 2.0: “Dry shippers” and vacuum packaging keep samples stable for up to 48 hours without liquid nitrogen.

- Super Cryo: Ultra‑thin “candy floss” films or micro‑droplet vitrification speed thawing and boost motility.

- Home Analysis Kits: Smartphone‑based sperm checks and microchip motility assays bring testing home.

- Blockchain Registries: Decentralized, tamper‑proof databases could track usage and origin of every sample.

- Polygenic Scoring Light: Risk scores for common genetic disorders—pragmatic instead of “designer baby” fantasies.

In short: technology is making sperm donation faster, more precise, and more global—from cell development in the lab to fully transparent documentation.

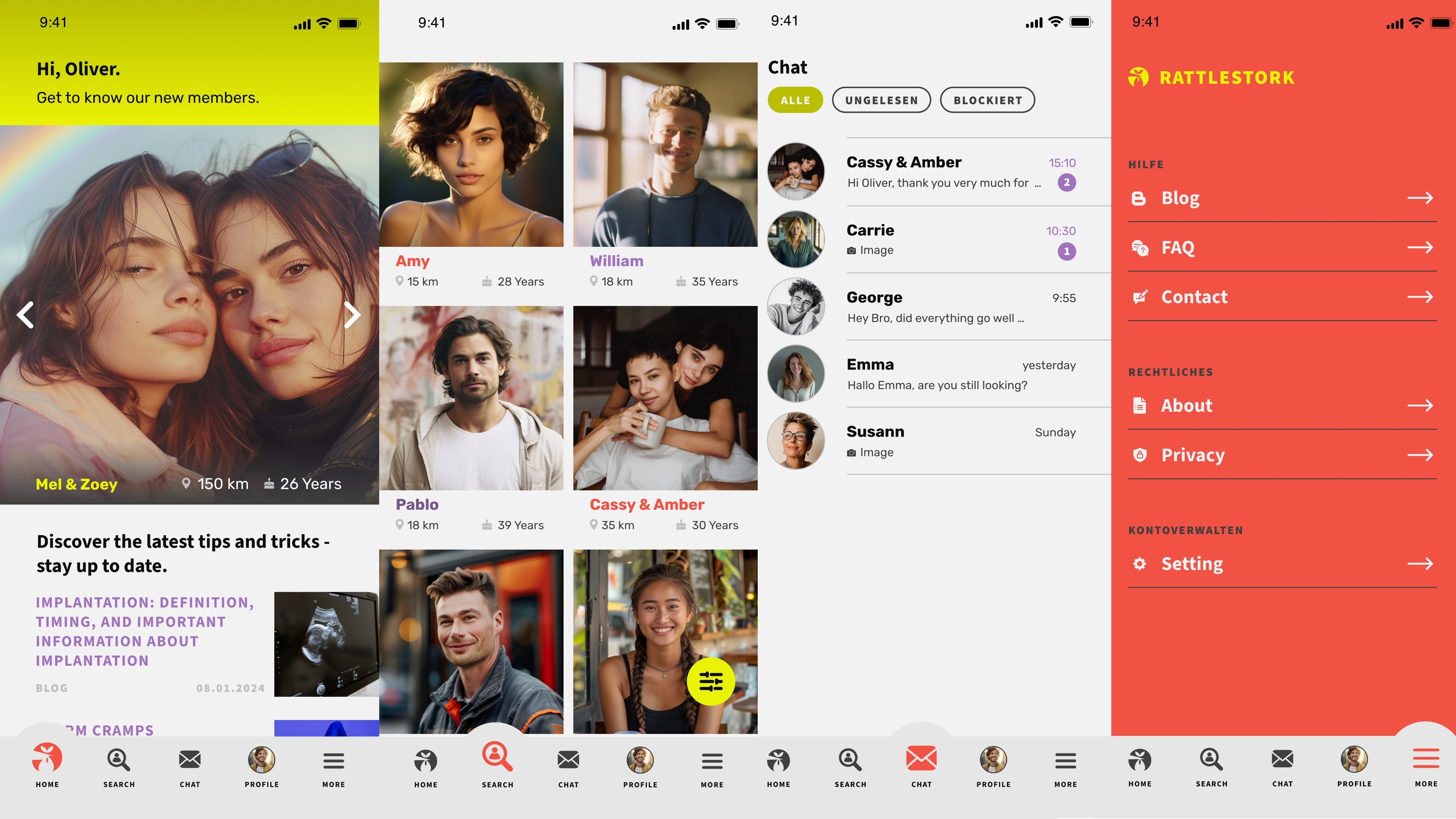

RattleStork – Community, Matching & Legal Guidance

RattleStork brings intended parents and donors together, offering filters and matching tools, prewritten contract templates, and community forums. Users decide which medical clearances they want to see— RattleStork provides the clear platform to make it happen.

Conclusion

From Spallanzani’s dogs and glycerol breakthroughs to millionaire‑run sperm banks and DNA detective work, the history of sperm donation is rich and surprising. Today, more information, tools, and connections are at your fingertips than ever before. That’s what modern sperm donation is all about: knowledge, choice—and the freedom to find your path.